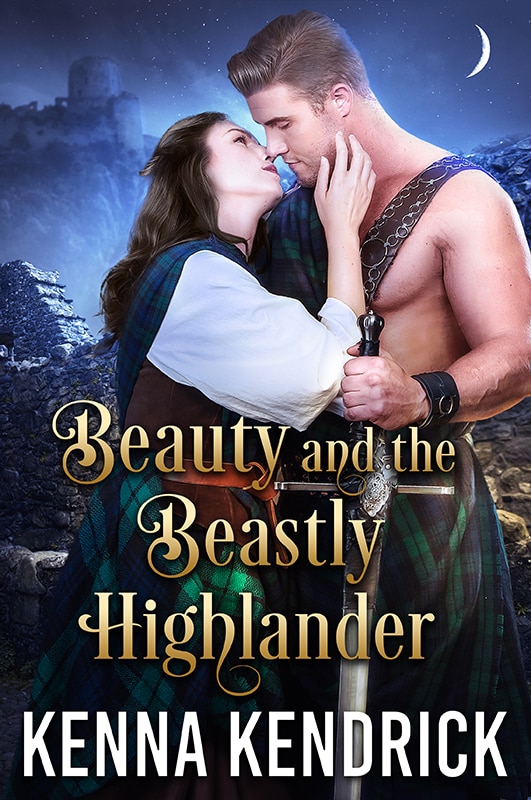

Beauty and the Beastly Highlander (Preview)

Chapter I

Etna sat by the window of her father’s study, the hefty book in her lap long forgotten. She was staring at her father, who was looking at her with such a pleased smile that it only served to infuriate her even more.

“What makes ye think that I wish to tutor Laird MacAlistair’s daughter?” she asked him as she stood and crossed her arms over her chest defensively. Her father hadn’t even asked her. He had simply announced that he had accepted the offer on her behalf.

“All yer life ye wished to be a tutor,” her father, Dougal, reminded her. “Ye were but ten years of age, and ye always said ‘Dadaidh, I wish to be a tutor like ye when I grow up.’ Weel, ye’re all grown up noo, and Laird MacAlistair asked specifically for ye.”

That was another thing that Etna didn’t understand. “Why would the Laird ask for me?”

“Because he kens ye’re me daughter,” her father said. “And he kens that ye’ll teach his daughter weel, like I taught him weel when he was but a bairn. He wants someone he can trust, and he trusts us. Ye should be honored that he asked for ye.”

Honored. What is honor compared to fear?

Etna had heard everything there was to hear about Laird MacAlistair. It was hard to live under his rule and not know that he was an unpleasant man at best, a cruel man at worst. There were rumors about him that Etna couldn’t simply ignore, tales of his brutality that made her skin crawl. Everyone called him Beast because of his viciousness and his allegedly disfigured face that made mirrors break and children run to their mothers.

That’s what happens to evil men, Etna had heard one of the old women in the village say. Their evil shows on their face.

Of course, Etna didn’t believe in that. She knew enough about the world, had read enough books, and studied enough subjects to know that it was nothing but old wives’ tales. That was one of the reasons why she hated being in that village so much. Everyone was close-minded and wouldn’t even consider the possibility that the Laird had simply had an accident or had been wounded in some other way. They had a superstition for everything, and when Etna tried to tell them that they were wrong, she feared that they would hang her as a witch.

“Ye’ve wanted to leave this village ever since we came here,” her father reminded her. “Noo is yer chance.”

“Faither, I wished to go back to Edinburgh,” Etna reminded him. “Na the Laird’s castle. I want to go back home. I want to go back to the city.”

“Ye ken that we canna do that.”

Etna fell back down onto the chair with a sigh. Every time the two of them had that conversation, her father always told her the same thing: they couldn’t return to Edinburgh. Etna had tried to reason with him, telling him that she could work now, too, and that they would have two incomes to support themselves, but Dougal wouldn’t hear any of it. She was certain that it was more than their lack of money. She was certain that he had grown to like the quiet life of the village, but she couldn’t enjoy a single minute of it. Ever since they had left Edinburgh after her mother’s death, looking for a cheaper place to live, Etna had been dreaming about the moment that she would go back.

“Ye ken that bein’ a tutor for the Laird’s bairn is the best option ye have,” her father said as he walked up to her from behind his desk, perching himself on the windowsill next to her. “Ye always wanted to do this, Etna. Dinna let some rumors stop ye.”

“But everyone always says that the Laird is a terrible man,” Etna pointed out, looking at her father with wide, pleading eyes. “How can ye send me there when ye ken that?”

“Dinna listen to what everyone says,” Dougal told her, shaking his head. “I didna expect ye to believe what ye hear about the Laird. Ye ken how the people in these parts can be. Weel, I was his tutor when he was younger, and I ken that he’s a good man. I wouldna send ye to that castle if I thought that ye’d be in any sort of danger, Etna. I am askin’ ye to forget everythin’ that ye’ve heard about him until ye meet him yerself. Ye can make yer own judgment.”

“And ff me own judgment is the same as everyone else’s?” Etna asked.

With a sigh, Dougal patted her shoulder with a gentle hand. “Then ye’ll leave the castle and return here. I willna force ye to do anythin’ that ye dinna wish to do. I’m only askin’ ye to give the Laird a chance.”

The assurance that she could always return to her father put Etna at ease. It was good to know that if the Laird turned out to be a horrible man, she could always leave the castle, that she would always have a place with Dougal.

I should be grateful, really. I should be thankin’ him.

Her father had always been the most important person in her life, and he had always been so understanding, so accepting of everything that she wanted to do. He had taught her everything that she knew, and not once had he pressured her to marry. Some of her friends—bright, promising young women—had been lost to marriage, and she had no intention of heading down the same path.

And now, all that he was asking of her was to follow her dream to become a tutor, to guide a young life and teach it everything that she knew. She had the chance to do what she had always wanted to do, and she had almost turned it down because of some rumors.

“Alright,” she said, a small smile spreading over her lips. “I suppose that I can go to the castle and see how it is to live there. But I’m warnin’ ye, Faither . . . if I dinna like bein’ there, I will leave.”

“I have no doubts about that,” her father said, giving her a smile of his own as he stood, heading back to his chair.

Etna watched him for a few moments. Though his brown hair had started to grey at the temples, his eyes were as bright as ever, the same green as her own. At fifty-five, he was still young and sprightly—though a little pudgy from avoiding manual work—but he had never been alone before in his life. Etna had always been there for him, and he had always been there for her. The two of them had been taking care of each other ever since her mother had passed, leaving them all alone.

Will he be alright on his own here? What if he needs me help? Me company? How am I to leave him all alone?

It was an excuse, Etna knew, but she didn’t want to admit it. Unlike her, her father was quick to make a friend out of everyone he met, and he was anything but alone in the village. It was rare that it was just the two of them in the house, as people were coming in and out throughout the day, her father’s guests, all of them seeking his company.

The truth was that she was lonelier than he was. She wasn’t particularly shy, and she had had plenty of friends in Edinburgh, but the feelings of hopelessness had isolated her from those around her when she had moved to Beninroch, a remote little village three days’ ride from Inverness. Now, she thought it was too late to make a good impression on her neighbors.

Perhaps a fresh start is precisely what I need. Goin’ to the castle where no one kens who I am, where I may make some friends.

And after all, she could always visit her father. The castle wasn’t that far from the village, and she would make it clear that as long as she tutored the Laird’s daughter as agreed, she would be allowed to do as she wished.

“When am I required to be there?” Etna asked her father. Now that the decision had been made, she would have to get everything in order before she could leave. Although what exactly there was for her to do in that house, in that village, she didn’t know. She simply didn’t want to leave before ensuring that her father would be fine.

“As soon as possible,” Dougal told her. “Ye can leave the morrow if ye so wish.”

“The morrow?” Etna exclaimed. “It’s much too soon, Faither. What about ye?”

“What about me?”

“Weel . . . we dinna have much wood left in the house, and what about meat and—”

Dougal stopped her by raising a finger, shushing her. “Etna, I am perfectly capable of getting me own wood and meat, lass. Ye dinna have to worry about me. Ye’ve worried about me for too long. It’s time that ye leave this place.”

Etna didn’t bother telling her father that as much as she wanted to leave the village, she didn’t particularly want to go to the MacAlistair clan castle. There was only one place where she wanted to go, and that was Edinburgh, as she knew that no matter where she went, as long as she was in the countryside, the people surrounding her would be close-minded. She had had enough of people who thought that she couldn’t teach because she was a woman and that the only thing she was good for was marriage. But the two of them had had many arguments about it, and she never did manage to reason with him. She was wasting her breath, repeating it to him, and so she remained silent.

But perhaps if I do weel with the Laird’s daughter, he will give me the means to go to Edinburgh. Perhaps, I could negotiate with him.

That thought grew in Etna’s mind within moments, and suddenly, she had a plan. She would go to the castle, would do her best to teach the Laird’s daughter, and, once she saved up enough money, she would finally go back home, to her real home, to Edinburgh. And by then, she thought, she would surely have the credentials to teach many other children, and she could bring her father with her. He wouldn’t have to worry about his finances anymore.

“What are ye smilin’ about?” her father asked her, pulling her out of her thoughts. When Etna looked at him, she noticed that he was smiling, too, as though her own smile was contagious.

“Nothin’,” she lied. She decided that her father didn’t need to know about her plans, in case he loved the village as much as she suspected, and tried to put an end to them. “I’m only thinkin’ about the travel to the castle.”

From the look that Dougal gave her, Etna thought that he didn’t believe her, but thankfully he didn’t push her for a more truthful answer. Instead, he went back to his papers, and Etna went back to her book, feeling happier than she remembered being in a while.

It wasn’t only happiness, though, she noticed. It was hope too.

That night, she could hardly sleep, spending the hours staring at the ceiling and waiting for daylight to come. The prospect of returning to her beloved home had left her too excited to sleep, and all she could do was count the minutes until she could grab her horse and head to the castle.

***

At the first light of the morning, Etna stood from her bed, throwing the belongings that she needed in two bags. Before doing anything else, she headed to the study, knowing that her father would already be there.

She found him behind his desk, hunched over it. In front of him, he had her favorite book, the one that he read to her every night when she was young, and he didn’t seem to notice her as she entered. Etna watched him in silence, a flood of emotions overtaking her.

She would miss her father terribly, and she knew that the same would be true for him. If he asked her to stay, Etna would, but she knew that he would never do that. He wanted her to find her own place in the world, he had told her once. He wanted her to live her own life, and that meant that she would eventually have to leave him behind, at least for a while.

When Dougal noticed her, it startled both of them. Etna didn’t know how long she had been standing there, by the door, watching him, but she had forgotten that she was there.

“What are ye doin’, lass?” her father asked, his hand clutching his chest in his fright. “Ye almost scared me to death.”

“I didna want to bother ye,” she told him with a small shrug.

“Ye’re never a bother, Etna,” he said, and his voice was quiet, as though even the smallest sound could shatter the moment between them. “Are ye ready, then?”

Etna nodded, the words sticking to her throat, refusing to come out. Dougal approached her with a small smile, placing a hand on her shoulder.

“Ye ken that na matter where ye are, ye’ll always have me,” he said. “And it willna be long until I see ye again. Once ye’re settled, I’ll come to visit ye.”

“Promise?” It was all Etna could say, and even that one simple word sounded broken.

“I promise. Dinna fash yerself. The castle isna that far! I can visit ye, and ye can visit me.”

That promise lifted Etna’s spirits enough to bring a smile to her lips. As painful as it was to leave, she held onto that hope that she would see him again soon.

With that, her father let his hand fall off her shoulder, his gaze coming to rest on the two bags in her hands. He took both from her and began to walk to the door, nodding his head as an invitation for Etna to follow.

She could hardly believe that the time had come for her to leave. She let her father strap the saddle onto her horse and then the bags onto the saddle, the entire time searching for the right words to say, only to find that there were none. She didn’t know how to say goodbye. They had never been apart, and the time had come too soon.

I wish he could come with me. I’ll need him more than ever when I am in that castle.

Etna averted her gaze when her father approached her, wrapping his arms around her. She clung to him, but she didn’t dare look at him, knowing that the moment their eyes would meet, she wouldn’t be able to hold back the tears.

“I’ll miss ye, Faither,” she said, trying to keep her voice steady, even as her hands shook. “I’ll write to ye often, I promise.”

“I’ll miss ye, too,” her father said, and he sounded more emotional than Etna had ever heard him before. Once he let her go, she noticed that he, too, averted his gaze, and she wondered if it was something that she had inherited from him, that refusal to cry in front of others. “Weel . . . it’s time to go noo. Ye dinna want to be out all alone when it’s dark.”

Etna nodded in agreement, but her legs were lead and wouldn’t move. Her father must have noticed as he gave her a small, sad smile and made his way out of the stables. Etna saw him head back to the house, and only then could she bring herself to mount her horse.

As she rode toward the edge of their property, she turned her head and looked back at the house. Her father stood in front of the door, waving at her.

She whispered a promise in the wind to see him again soon.

Chapter II

“I just dinna understand how this always happens if there is na a traitor among us,” Finley said, slamming his fist onto his desk. “Every time we go after the brigands, they manage to escape. Every single time, Lochlan. We’ve never caught even one of them.”

Lochlan, his brother, stood with his back to Finley, staring out of the study window. Finley was the Laird of the MacAlistair clan, but he didn’t feel safe even in his own castle. His study was the only place left where the two could talk without Finley worrying that they would be heard by a traitor.

“I dinna ken what to tell ye,” Lochlan said with a heavy sigh. “I agree with ye, I do, but what are we to do? We’ve tried everythin’. I canna go to the men and accuse them of bein’ traitors!”

Lochlan was right, of course. Finley had refrained from making any accusations. Even though he wasn’t as close to the men as he used to be some years prior, he couldn’t imagine that any of them would betray him. He knew all those men ever since they were all children. It made no sense to him that one of them was a traitor, but it was the only logical conclusion he could reach.

“The clan is fallin’ apart in front of me own two eyes, and there isna a thing that I can do to stop it,” Finley said, his hand coming up to curl around a cup of wine that he had finished too soon. He tipped the carafe over it and found that empty, too, which only served to infuriate him even further. “I am their Laird, and I can do nothin’ but sit back and watch as those brigands destroy our lands.”

The look that Lochlan gave him was not one of pity, as Finley had been expecting, but rather one that spoke of how unimpressed he was. Despite his anger, Finley didn’t say anything. Even without speaking, he knew what Lochlan was thinking, and he knew that he had a point.

Ever since Anna, his dear wife, had passed, he had withdrawn from everything and everyone. The clansmen had no trust in him anymore. The village people in his land had no trust in him either, and he had heard of their unsavory nickname for him: Beast.

That was how they thought of him, and, perhaps, that was precisely what he was. The burden of the past he was carrying made him less and less human every day, chipping away at his soul.

“What do ye want me to do?” Lochlan asked. “Anythin’ ye want, I’ll do it. But we must come up with a plan before we accuse any of the men of bein’ a traitor to the clan.”

“Aye, I ken,” Finley assured him. “And I dinna have a good guess as to whom it could be. Yer guess is as good as mine. I can hardly believe that any of our men would do such a thing.”

Lochlan gave him a slow, understanding nod as he walked back to his chair, falling onto it with a sigh. “The most important thing right noo is to protect the villages. The brigands have been stealin’ from our people and killin’ our men for too long. They’ve tried to defend themselves, but there’s na much they can do. They’re na trained. They have na weapons. They are na match for the brigands.”

“We canna send men to every village,” Finley pointed out. “Perhaps we can spare a few and send them to the biggest ones, but there is na a thing we can do for the smaller ones unless we can finally fight them. But how will we fight them if they always run to the mountains?”

“We’ll find a way,” Lochlan assured him, but Finley could tell that he wasn’t as certain as he wanted to sound. “But Finley . . . ye must speak to the people. Ye’ve spent too long away from them. I’m surprised they even remember that ye’re their Laird.”

Finley shook his head. Lochlan already knew that he couldn’t do such a thing, and he also knew why. He couldn’t bear to be out there. He couldn’t bear to speak to anyone. Even though it had been five years since his wife’s death, it still haunted him, and he had not felt joy since. The mere thought of talking to his people, of touring the land and trying to get everyone to like him again, was exhausting. He would much rather stay in the castle and leave everything that had to do with people on Lochlan. After all, his brother had always been the social one, the one that constantly attracted people.

“Ye willna do it.” It wasn’t a question as much as a statement, and Finley looked up to see Lochlan shaking his head at him in disappointment.

“I canna.”

“Ye willna,” Lochlan insisted. “Weel . . . at least come with us on the hunt.”

Finley frowned at that. “The hunt?” he asked. It was the first time that he was hearing of it. “What hunt, Lochlan?”

“Weel, me and a few of the lads are goin’ huntin’,” Lochlan said with a small shrug.

“Noo?” Finley asked. “Do ye really think it’s a good time to be huntin’? I’d rather hunt the brigands than boars.”

“Weel, ye canna hunt the brigands until they show their faces again,” Lochlan pointed out. “And it’s good for the men. It keeps them in shape. It’ll do ye plenty of good, too, ye’ll see. Ye’ll get some fresh air.”

“I can walk around the castle grounds to get fresh air, thank ye,” Finley said, but the mischievous smile on Lochlan’s lips told him that he wouldn’t simply let it go. Finley knew his brother well; when he got an idea in his head, it was impossible to get it out. “Must I?”

“Na, but I think that ye should,” Lochlan said. “Ye’re the Laird . . . I canna force ye to do anythin’ ye dinna want.”

“But?”

“But ye’re also me brother, and I can annoy ye into comin’ with us.”

Finley knew that to be true. Reluctantly, he nodded his head, thinking that it would be easier to simply do as Lochlan wanted instead of fighting him over something so silly. Besides, perhaps it would be good for him in the end, he thought. He couldn’t remember the last time that he had left the castle, and he certainly couldn’t remember the last time that he had spoken to any of his men about anything other than clan business. Ye have to bond with them, Lochlan always said. Ye have to show them that ye care.

The truth was that Finley did care. He cared about his clan, about his people, and there had been a time when everyone had known that. There had been a time when no one called him Beast, when his people loved him, and the brigands feared him. There had been a time when he could look his clansmen in the eye. But that time was long gone, and now all was left was that guilt that was eating him up alive.

“Excellent,” Lochlan said as he stood once more, this time heading for the door. “We’ll be leavin’ the morrow at first light, so make sure that ye get some rest tonight.”

With that, Lochlan was gone, shutting the door behind him, and leaving Finley alone with his thoughts once more.

As much as he couldn’t stand being around people, he also hated being alone. It meant that he had too much time to think, too much time to consider what could have been different if his wife was still alive, what he had lost. In all those five years, he had barely even managed to talk to his daughter, and it was only getting worse. He couldn’t remember when he had last spoken to her. He had just left her in his grandmother’s hands, letting her raise her as she saw fit.

I’m a failure. I canna even do that right.

At least his grandmother would raise Malina well, that much he knew for certain. She was the closest thing that the girl could have to a mother figure, after all, and Finley knew that she was better off with her than with him. He was in no condition to care for a child.

Finley drained the rest of the wine that Lochlan had left behind before retiring to his chambers. The room always seemed so big to him without Anna in it, and it was no different now. He was used to being all alone, though, and he preferred it that way. Most of his nights were sleepless, and the moment that his head hit the pillow, he knew that he wouldn’t be resting much.

***

The morning came later than he would have liked, and by the time the first light broke in the horizon, Finley had slept very little after tossing and turning all night, like most nights. Still, he stood and dressed before heading outside to find Lochlan and the rest of the men who would join them on their hunt.

He wasn’t surprised to find that none of them was there yet. Perhaps they were having breakfast, he thought, or perhaps they were still getting ready, but Finley didn’t want to go back inside. At that time of the morning, the courtyard was still mostly empty, save for the few servants who were going about their day, having woken up before dawn. They didn’t dare look at Finley, anyway, let alone talk to him. They all knew to not disturb him and always kept a good distance from him.

No one wanted to face his wrath.

Finley had to admit that he was short-tempered, but not as much as those around him wanted to think. How could they have forgotten what he was like before Anna’s death, he wondered? How could they all think that he was a monster now? He was not the same man, but he wasn’t cruel.

“He came!” Lochlan exclaimed, his voice carrying across the courtyard. Finley turned his head to look at him and saw that there were six of their men with him, all of them ready for the day’s adventure.

“I did,” Finley said, as the men bowed in a chorus of “Me Laird’s”, rushing to greet him. They respected him, but it was a respect that stemmed from fear and knowing that left a bitter taste in Finley’s mouth. “Ye did threaten to annoy me, and I ken that ye can, so I decided that this would be less painful.”

“Only if ye dinna get run down by a boar, brother!”

Lochlan began to run to the stables, cheerful as always. Though he had the same blonde hair as Finley, he was shorter, and he had inherited their mother’s honey-brown eyes. He had also inherited her charm and her joyful disposition, it seemed.

Finley envied him for that. No matter what, Lochlan always managed to see the bright side, not letting every bad thing that had happened to him weigh him down. Then again, his woes were nothing compared to Finley’s own. He had never lost a wife. He had never had to carry a past that dragged him down daily. He didn’t have a daughter that he couldn’t face or people who hated him. He was loved by everyone, and though Finley sometimes envied him, he couldn’t help but adore him, too.

Finley listened to his men as they chatted while they walked to the horses. Once they were on their way, he fell in step next to Lochlan, who was already loud and lively, shouting with a cheer that seemed inexhaustible.

It had been a long time since Finley had banned his clansmen and women singing and laughing in the hopes that he wouldn’t have to be constantly reminded about everyone else’s happiness when he was so unhappy. And yet, Lochlan always found a way to let everyone know just how jolly he was, much to Finley’s chagrin.

“Me Laird!” Lochlan yelled, startling Finley. “Would ye care for the finest wine that our clan has to offer?”

Finley rolled his eyes at his brother, but he took the flask that he had offered to him. It never did any good to refuse a good wine, or bad wine, for that matter. Taking a swig, Finley passed the flask back to him, wincing at the burn in his throat.

“That’s na wine,” he told Lochlan.

With a frown, Lochlan looked at the flask. “Na?” he asked. “Ach, it might be whiskey. Weel, it’s better than water, that’s for certain!”

Finley gave his brother an unimpressed look. Lochlan was one of the two people—the other being their grandmother—who wasn’t afraid of him, and so his look didn’t have much of an effect on him, but it was enough to stop the conversations among the other men. They all fell silent, and Finley soon found that he preferred it that way.

His men knew better than to look at him, but in the sudden silence, Finley felt exposed. There was nothing to distract them anymore, and so he pulled his hood over his head, eager to hide. The scar that he had gotten on his face the day that Anna died wasn’t something that he wanted people to see, not even the people closest to him.

He didn’t even want to look at himself in the mirror anymore. The scar was a constant reminder of what Anna had done.

“This is a good spot,” Finley heard Lochlan say, and they all stopped, dismounting their horses, and tying the reins around the nearby trees. It wasn’t much later when they spotted a boar in the distance, and Finley immediately rushed toward it, disregarding the warnings that everyone yelled after him. He knew that hunting boars was a dangerous sport, but he had done it many times before.

And a part of him simply didn’t care.

Running after the animal gave him a rush that he hadn’t felt in a long time. He felt alive again, his mind ridding itself of every other thought. All that mattered at that moment was that boar and his own survival. His baser instincts took over, providing momentary relief from the endless noise that were his thoughts and worries.

He couldn’t hear any of his men behind him. He didn’t know if they were there, if they had followed him or if they had lost him in the woods as they ran. All he knew was that nothing would stand between him and that boar.

If you want to stay updated on my next book, and want to know about secret deals, please click the button below!

If you liked the preview, you can get the whole book here

If you want to be always up to date with my new releases, click and...

Follow me on BookBub

Good start….I want more! BTW Beauty and the Beast is my favorite Fairytale!

Thank you my dear Sharon. It`s a wonderful story indeed 😉

Intriguing beginning, can’t wait for the rest

Thank you my dear Angela. Stay tuned for more 😉

I have a feeling that Etna’s life is about to get a whole lot more interesting and Finley is going to get a wake up call that brings him out of his loneliness. Quite a different beginning for this adventure.

Thank you my dear Young at Heart. All will be revealed in time 😉

I am excited for the release. I am new reader of your novels. So far you have not disappointed me.

Thank you my dear Karen. I am really glad that you liked it 🙂

Dang it! I wanted to see them meet!!! Great start. Thanks for the sneak peek!

Thank you so much my dear Tina. I am really glad that you liked it 🙂

Can’t wait to read the rest of this story.

Thank you my dear Debra. Stay tuned for the rest 😉

Think her and his lives are about to change forever along with his daughter.

Thank you for the message my dear Donna. It remains to be seen 😉

She is on her way to the castle and he is on his way to hunting. The boar has been sighted. Who will get to the boat first, the lady or the laird? I have a feeling someone will be needing a rescue. I am curious. Can’t wait to read the rest.

Thank you my dear Marisu. It remains to be seen 😉 Glad that you liked it 🙂

This book has ‘possibilities’. The 2 main characters have not met but the drams seems to be building between a very unhappy man and his clan members.

Thank you my dear Polly. Glad that you liked it 🙂

Looks interesting can’t wait to see more

Thank you my dear Carrie. Stay tuned for the rest 😉

I want to read the rest of the book – how may I download? Thanks 0

Thank you my dear Ret. The book is close to its release 🙂 Stay tuned 😉